History of Dunaverty

Dunaverty

The name is Gaelic, and several interpretations have been suggested, including Dun Abhartaigh, the Fort of the Abhairtach, an ancient powerful tribe.

Gaelic was the customary language in Kintyre from about the 5th century AD until the 17th century, when Scots speaking families from Ayrshire and Renfrewshire were settled in the southern part of the peninsula.

There were still a few Gaelic speakers in Southend even into the mid-20th century.

Dunaverty

The name is Gaelic, and several interpretations have been suggested, including Dun Abhartaigh, the Fort of the Abhairtach, an ancient powerful tribe.

Gaelic was the customary language in Kintyre from about the 5th century AD until the 17th century, when Scots speaking families from Ayrshire and Renfrewshire were settled in the southern part of the peninsula.

There were still a few Gaelic speakers in Southend even into the mid-20th century.

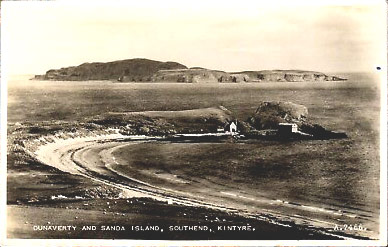

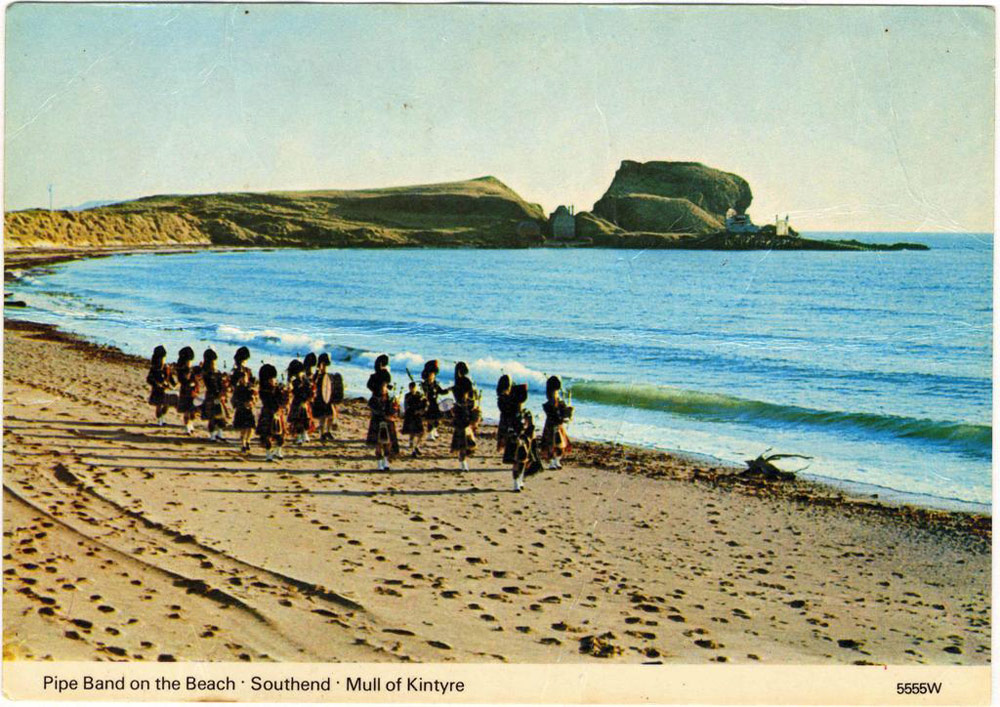

A natural stronghold

Dunaverty was an obvious choice for fortification. Formed on conglomerate rock, it is a natural stronghold, being protected on three sides by cliffs and sea. The summit is accessible only from the north, across a narrow path.

Photo credit: OwdJockey, Scottishhills.com

A natural stronghold

Dunaverty was an obvious choice for fortification. Formed on conglomerate rock, it is a natural stronghold, being protected on three sides by cliffs and sea. The summit is accessible only from the north, across a narrow path.

Photo credit: OwdJockey, Scottishhills.com

Dunaverty Castle

As a fortification, Dunaverty has had a long and interesting history. It is first mentioned in The Annals of Ulster, which record that Aberte was besieged there by Sealbach, King of Dalriada, in AD 712.

About 1250, the castle was stormed by John Bisset in the service of King Henry III of England. In 1263, it was garrisoned by King Alexander III of Scotland against the invasion of King Haco. It was, however, surrendered to Haco, who placed it under the command of a fellow Norwegian, Guthorm Backa-Kolf.

Image left: Reconstruction by Andrew Spratt

Dunaverty Castle

As a fortification, Dunaverty has had a long and interesting history. It is first mentioned in The Annals of Ulster, which record that Aberte was besieged there by Sealbach, King of Dalriada, in AD 712.

About 1250, the castle was stormed by John Bisset in the service of King Henry III of England. In 1263, it was garrisoned by King Alexander III of Scotland against the invasion of King Haco. It was, however, surrendered to Haco, who placed it under the command of a fellow Norwegian, Guthorm Backa-Kolf.

Image left: Reconstruction by Andrew Spratt

Robert the Bruce

The castle, a little later, was taken over by Angus Og MacDonald of Islay and Kintyre, who there entertained Robert the Bruce for three days in the autumn of 1306, It was captured, soon after, by the English, who had expected to find Bruce there; but he had already made his escape.

Angus Og – Young Angus – advanced the fortunes of the powerful Clan Donald by backing Bruce at the decisive Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, commanding the men of Kintyre and Islay.

Clan Donald, however, as Lords of the Isles – and Kintyre – was to come increasingly into conflict with the Scottish Crown, and was finally dispossessed of its lands in 1493 by King James IV.

Image: Statue of Robert the Bruce

Robert the Bruce

The castle, a little later, was taken over by Angus Og MacDonald of Islay and Kintyre, who there entertained Robert the Bruce for three days in the autumn of 1306, It was captured, soon after, by the English, who had expected to find Bruce there; but he had already made his escape.

Angus Og – Young Angus – advanced the fortunes of the powerful Clan Donald by backing Bruce at the decisive Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, commanding the men of Kintyre and Islay.

Clan Donald, however, as Lords of the Isles – and Kintyre – was to come increasingly into conflict with the Scottish Crown, and was finally dispossessed of its lands in 1493 by King James IV.

Image: Statue of Robert the Bruce

King’s Governor hanged

In the following year, King James stayed at Dunaverty Castle, which he re-fortified with cannon and in which he installed his own governor. In an astonishing act of defiance, Sir John Cathanach MacDonald, who had expected his Kintyre lands, and the castle itself, to be restored to him, took the castle by surprise, with only a small body of men, and hanged its newly appointed governor over the walls in full view of the King, who was offshore in his boat.

MacDonald then fled to the Glens of Antrim in Ireland – a customary bolt hole for Clan Donald renegades – but was subsequently betrayed by a kinsman and hanged along with other members of his family.

Image left: James the IV King of Scotland. Credit.

King’s Governor hanged

In the following year, King James stayed at Dunaverty Castle, which he re-fortified with cannon and in which he installed his own governor. In an astonishing act of defiance, Sir John Cathanach MacDonald, who had expected his Kintyre lands, and the castle itself, to be restored to him, took the castle by surprise, with only a small body of men, and hanged its newly appointed governor over the walls in full view of the King, who was offshore in his boat.

MacDonald then fled to the Glens of Antrim in Ireland – a customary bolt hole for Clan Donald renegades – but was subsequently betrayed by a kinsman and hanged along with other members of his family.

Image left: James the IV King of Scotland. Credit.

The massacre of 1647

But the most horrific episode in the castle’s bloody history was still to come – the infamous massacre which took place there in June of 1647, when both England and Scotland were being torn apart by civil war.

The Royalist army of the legendary warrior Lieutenant General Sir Alexander MacDonald – in Gaelic, Alasdair MacColla – being pursued and harried by the Covenanting force of General David Leslie, split in two at Rhunahaorine in North Kintyre.

MacColla and many of his men escaped to Islay in boats, while the remainder continued south, under the command of Archibald Mor (‘Big’) MacDonald of Sanda. They went as far south as they could, which was Dunaverty Castle, and there awaited their fate.

Image right: © Credit Becky Williamson

The massacre of 1647

But the most horrific episode in the castle’s bloody history was still to come – the infamous massacre which took place there in June of 1647, when both England and Scotland were being torn apart by civil war.

The Royalist army of the legendary warrior Lieutenant General Sir Alexander MacDonald – in Gaelic, Alasdair MacColla – being pursued and harried by the Covenanting force of General David Leslie, split in two at Rhunahaorine in North Kintyre.

MacColla and many of his men escaped to Islay in boats, while the remainder continued south, under the command of Archibald Mor (‘Big’) MacDonald of Sanda. They went as far south as they could, which was Dunaverty Castle, and there awaited their fate.

Image right: © Credit Becky Williamson

It was to be a hard fate. Leslie and his army laid siege to the Castle and immediately cut off its water supply by capturing an outer ditch or defence. When the garrison surrendered, a few days later, it was massacred with few exceptions.

Most of the estimated 300 men who had been holed up in the tiny castle were from Kintyre and other parts of Argyll, and included many MacDougalls.

The inscription on the memorial pictured right reads:

“This enclosure was erected by the Rev. Douglas Macdonald, XIIth Laird of Sanda, in 1846 to mark the spot where his ancestors Archibald Mhor and Archibald Oig, father and son, were shot and buried after the battle of Dunaverty in 1647. Other human remains found on the battlefield were interred here by him.”

It was to be a hard fate. Leslie and his army laid siege to the Castle and immediately cut off its water supply by capturing an outer ditch or defence. When the garrison surrendered, a few days later, it was massacred with few exceptions.

Most of the estimated 300 men who had been holed up in the tiny castle were from Kintyre and other parts of Argyll, and included many MacDougalls.

The inscription on the memorial pictured right reads:

“This enclosure was erected by the Rev. Douglas Macdonald, XIIth Laird of Sanda, in 1846 to mark the spot where his ancestors Archibald Mhor and Archibald Oig, father and son, were shot and buried after the battle of Dunaverty in 1647. Other human remains found on the battlefield were interred here by him.”

Flora MacCambridge

The young grandson of Archibald Mor MacDonald, according to local tradition, was smuggled to safety by his nurse, Flora MacCambridge. The infant’s father, Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Og (‘Young’) MacDonald, was killed later that year in the battle of Knocknanuss in Munster, Ireland, during which Alasdair MacColla himself was also slain.

Dunaverty Castle is thought to have been demolished in 1685, thus ending a long and distinguished history. Visible remains are scant, but on the south-western face of the rock a small section of lime and rubble wall, probably built to block a potential route of ascent, can be plainly seen.

Image right: Credit

Flora MacCambridge

The young grandson of Archibald Mor MacDonald, according to local tradition, was smuggled to safety by his nurse, Flora MacCambridge. The infant’s father, Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Og (‘Young’) MacDonald, was killed later that year in the battle of Knocknanuss in Munster, Ireland, during which Alasdair MacColla himself was also slain.

Dunaverty Castle is thought to have been demolished in 1685, thus ending a long and distinguished history. Visible remains are scant, but on the south-western face of the rock a small section of lime and rubble wall, probably built to block a potential route of ascent, can be plainly seen.

Image right: Credit

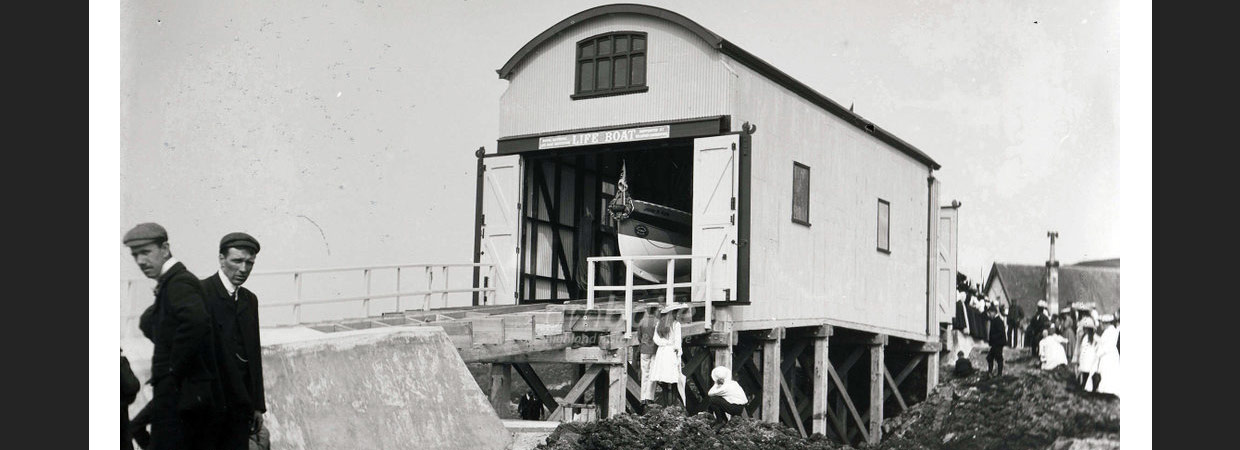

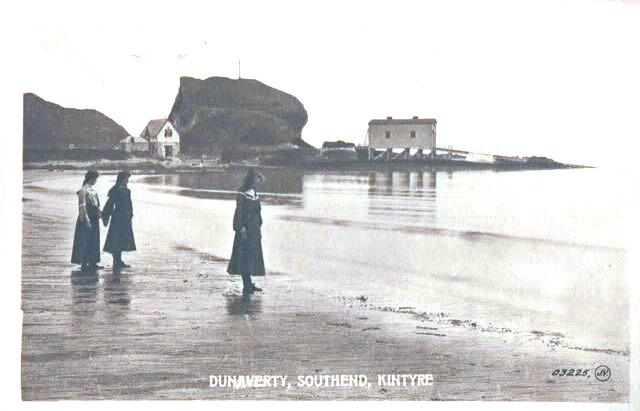

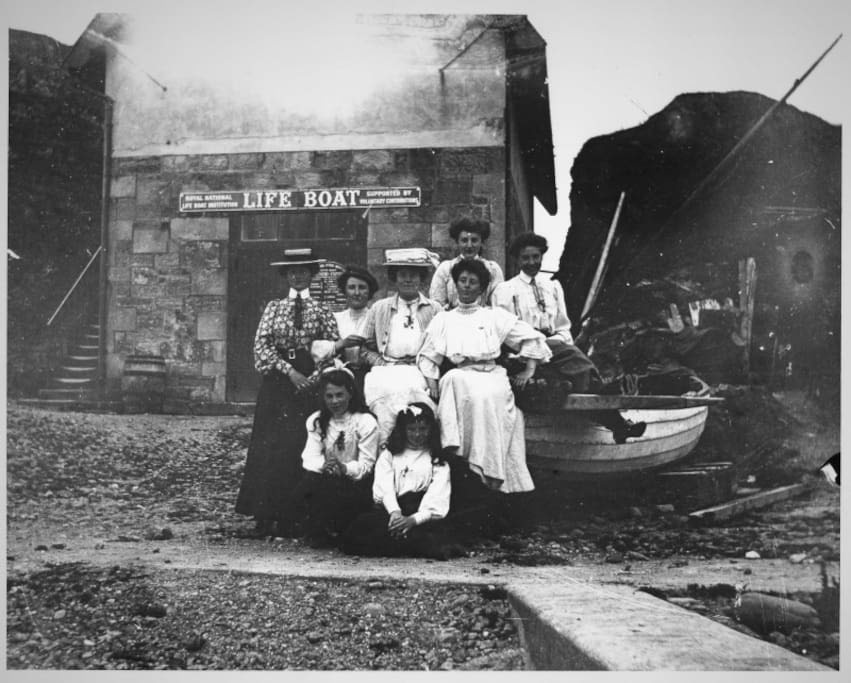

Lifeboat Station

The next substantial structure at Dunaverty, that we know of, was the National Lifeboat Institution’s lifeboat station, built in 1869, and still in place. The building has two stories. The lower one housed the lifeboat and the upper one accommodated the coxswain and his family.

The first coxswain was John Gillon, an Irish born fisherman who was brought up in the village: but the entire crew, latterly, came down from Campbeltown in a brake to answer call outs. The coxswain in 1906 was Henry O’Hara and the second coxswain, Charles Durnin, both Campbeltown fishermen.

Lifeboat Station

The next substantial structure at Dunaverty, that we know of, was the National Lifeboat Institution’s lifeboat station, built in 1869, and still in place. The building has two stories. The lower one housed the lifeboat and the upper one accommodated the coxswain and his family.

The first coxswain was John Gillon, an Irish born fisherman who was brought up in the village: but the entire crew, latterly, came down from Campbeltown in a brake to answer call outs. The coxswain in 1906 was Henry O’Hara and the second coxswain, Charles Durnin, both Campbeltown fishermen.

Both the station itself and the first Southend lifeboat, the 25 ft long, 10 oared John R Ker were presented to the NLI by Mr Robert Ker, merchant of Auchinraith in Lanarkshire, in memory of his son, who was drowned while duck shooting in Ronachan Bay, in north west Kintyre. The memorial tablet is still in place in front of the Boathouse.

The larger boatshed and slipway (derelict), closer to the Rock, were constructed in 1904 to accommodate a larger (38 ft) lifeboat, again named the John R Ker, the original slipway having been found to be useless in particular conditions.

Image left: Credit

Image below: 1905. The new lifeboat ‘The John R. Ker’, and the opening ceremony of the new lifeboat house. Image courtesy of Am Baile

Both the station itself and the first Southend lifeboat, the 25 ft long, 10 oared John R Ker were presented to the NLI by Mr Robert Ker, merchant of Auchinraith in Lanarkshire, in memory of his son, who was drowned while duck shooting in Ronachan Bay, in north west Kintyre. The memorial tablet is still in place in front of the Boathouse.

The larger boatshed and slipway (derelict), closer to the Rock, were constructed in 1904 to accommodate a larger (38 ft) lifeboat, again named the John R Ker, the original slipway having been found to be useless in particular conditions.

Image left: Credit

Image below: 1905. The new lifeboat ‘The John R. Ker’, and the opening ceremony of the new lifeboat house. Image courtesy of Am Baile

The wreck of the Argo

This defect was highlighted in February of 1903, when the Norwegian barque, the Argo, grounded on the Arranman’s Barrels reef and the Southend lifeboat crew ‘battled for hours to launch their boat, but time and again the craft was thrown against the beach by the great waves thundering upon the sands’. The surviving crew members of the Argo were finally rescued by the Campbeltown lifeboat.

The wreck of the Argo

This defect was highlighted in February of 1903, when the Norwegian barque, the Argo, grounded on the Arranman’s Barrels reef and the Southend lifeboat crew ‘battled for hours to launch their boat, but time and again the craft was thrown against the beach by the great waves thundering upon the sands’. The surviving crew members of the Argo were finally rescued by the Campbeltown lifeboat.

Changing times

After motor power became established in lifeboats, thereby increasing their speed and range, such outlying stations as Dunaverty became obsolete and were closed down.

The present owner of Dunaverty Boathouse and outbuildings is a local man who purchased the property in 1982. It had lain derelict for many years, lacked running water and sanitation and was in need of extensive renovation.

In 1989, the present owner of the Boathouse donated the station’s hand operated winch and a Lister diesel engine to the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine.

Changing times

After motor power became established in lifeboats, thereby increasing their speed and range, such outlying stations as Dunaverty became obsolete and were closed down.

The present owner of Dunaverty Boathouse and outbuildings is a local man who purchased the property in 1982. It had lain derelict for many years, lacked running water and sanitation and was in need of extensive renovation.

In 1989, the present owner of the Boathouse donated the station’s hand operated winch and a Lister diesel engine to the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine.